|

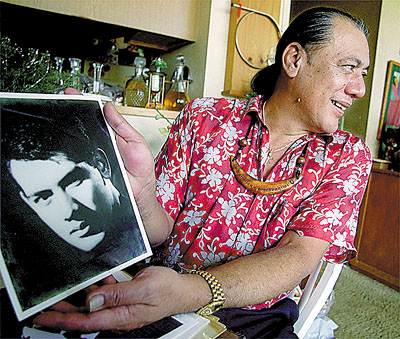

Tane Inciong, the oldest son, holds a photo of himself taken about a year after he graduated from St. Louis High School. The 57-year-old has seen the pendulum swing from assimilation to self-determination.

Bruce Asato • The Honolulu Advertiser

|

A voice for his family, a voice for his ancestry

Tane is the emerging patriarch of the Inciong family, the one with the geneaology charts, the scrapbooks and albums with family reunion photos, and the voice of conscience.

"He’s the one with the answers," said his 14-year-old nephew Tane McNeil.

At 57, the elder Tane, David Michael Kaipolaua‘eokekuahiwi II, has earned his stripes after living through territorial days, the patriotic drum roll for statehood, the peace and counterculture movement, the fight for self-determination and the Hawaiian cultural renaissance.

He was never a sign-carrying sovereignty activist. And after a rocky year of challenges to Hawaiian entitlements, he’s still not ready to take up arms for the cause.

"I prefer to educate people one on one," he said.

That doesn’t mean he’s not sharply tuned in to Hawaiian politics, or reticent to share his opinions. Lately Tane finds himself infuriated by the notion perpetuated by opponents that Hawaiians are racist and exclusionist.

He says that’s a smokescreen for the real issue - that Hawaiians are seeking redress for past injustices, so the healing can begin. "Racism is a Western disease, not a Hawaiian disease," he said.

Tane’s role model is his father, David Inciong Sr., who died Sept. 8, 1999, leaving formidable shoes to fill. "He taught us to stand up for our rights, but stick to the facts and not get overly emotional."

Tane shares his father’s full name. He was born in 1943 and raised in rural Wahiawa by strict but loving Catholic parents who discouraged their children from speaking pidgin in the home.

"My parents felt we should master the English language because we would have to compete in the white man’s world," he said.

He wanted to go to Kamehameha Schools, but his mother didn’t want him to go to a Protestant institution, so he settled for St. Louis High School, where his circle of friends included Frank De Lima.

In the 6th grade, a nun scolded him in art class for drawing an idol without a malo, and he experienced the clash of traditional Western aesthetics with his own Native Hawaiian expression.

Ethnicity was another source of confusion. As a young child he assumed "everyone was Hawaiian," but he was considered "cosmopolitan" because of his Hawaiian, European, Chinese and Filipino ancestry.

Then came the issue of patriotism.

Throughout his childhood, the prevailing ideology was one of assimilation to American culture. But Tane questioned authority. In 1959 he warned his parents against statehood, but they didn’t want to hear it.

"Hawaiian history was not taught in the schools. We were raised to be quiet, be patient, play the game," he said.

After graduating from high school in 1961, Tane entered a fine arts program at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, but dropped out after his third year to try his luck at working and pursuing a career in the arts.

During the swinging ’70s he was an entertainer in nightclubs and hotel resorts from Waikiki to Tokyo to Pittsburgh. A cross between Elvis Presley and Warren Beatty, his exotic look and honey baritone melted audiences as he sang such oldies as "Kaulana Na Pua" ("Famous are the Children") and Frank Sinatra’s "My Way."

Looking back, Tane said, he cringes at the stereotypes of Hawaiians and how the word "aloha" was twisted for the tourist industry. For his part, he seized every opportunity to correct misperceptions about Hawaiian history and culture.

Today, as Waikiki grows more distant from the old Hawai‘i of Tane’s youth, he feels nostalgic for a time when locals ran the place and people throughout the islands saw no reason to lock their doors.

Tane is still not much of a follower, and thinks it’s more important for Hawaiians to exercise their right to choose and be outspoken on the issue of sovereignty.

Deep in his na‘au (gut), he believes the responsibility of Hawaiians is to speak up for their ancestors, who were not heard.

"They want to be heard, and we have to address that," he said. "But the choice we make is going to be very different from the one they would have made. And that’s our choice, because times have changed."

|