Profile

• Living his Honolulu

Excerpts

• 50 years of telling our unique stories

Our Honolulu

• Questions remain on great adventure

Timeline

• Through the years

Photo gallery

• Images of Bob Krauss

Posted on: Monday, October 15, 2001

Living his Honolulu

By Beverly Creamer

Advertiser Staff Writer

"WOW!" comes an exclamation from across the room, drifting out of an office stuffed with enough Pacific artifacts to stock a small antique shop.

Advertiser library photo • 1956 As Bob Krauss rockets through the doorway, face animated, white hair flying, hardly an eyebrow lifts in the newsroom. The more sanguine among them have become familiar with the creative process at work in Hawai'i's best-known columnist. "LISTEN to THIS," he'll say, punctuating the latest anecdote with amazed and delighted laughter before retreating to pound it out. (He had to give up his old Royal typewriter because his shoulders finally gave in from hitting the keys so hard; today he uses a blue iMac). For a half-century, the man has bounded up a mountain of newspaper challenges. Cover the war in Vietnam? Walk around the Big Island re-enacting an early missionary journey? Sail off on the double-hulled canoe Hokule'a as storyteller for a new era in Pacific voyaging? In a heartbeat. "What's fun is not knowing what's going to happen," he says. "For years I'd look in the mirror and say 'I wonder who the hell you're going to be today.' " It was 50 years ago today that Bob Krauss began his career with The Advertiser. To work for five decades is a remarkable feat in any business, but it is especially rare in the exhausting, stressful practice of daily journalism where it's easy to lose your curiosity and your legs, and let the stories simply roll past. In an estimated 8,290 columns published since the early 1950s, Krauss has never lost his eagerness to uncover one more quirky piece of human nature, play a role in the big news story, or find the words that move his faithful readers to action or to tears. It would be easy to simply see Krauss, 77, as a quaint throwback to the days of the press-card-in-the-hatband gang immortalized in movies like "The Front Page." Indeed, he was one of the last holdouts when computers swept the newsroom and telephone technology turned digital. With his battered desk, typewriter, non-ergonomically correct furniture and 1920s candlestick phone, he surrounds himself with the trappings of history. But while Krauss may be a history buff, he's no historian, and he remains fully involved in writing about the news of the day in his twice-weekly columns. Most recently, he shared with readers his struggle to write a column after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, trying to find the balance between his usual lighthearted observations and acknowledgement of the despair weighing on Americans. "I'm a confirmed optimist," he says, "because pessimists are always wrong. How many times have they predicted the end of the world and gone to the top of the hill and waited for it and had to come down again?" When he proposed to former Advertiser publisher Thurston Twigg-Smith in 1973 they take a 30-day walk around the wild coastline of the Big Island as early missionaries had done, Twigg-Smith said, "You're crazy, Krauss." But he was intrigued, and that led to treks around several islands, and a Krauss book, "The Island Way," exploring the unique philosophies of those who live on islands. A war story Advertiser library photo • 1959 Even today, Krauss' stories of the three months he spent in Vietnam in 1967 are riveting. Hunkered down in foxholes, jumping off landing craft, skulking through rice paddies, notebook in hip pocket, he wore no helmet, no flak jacket, no backpack. Instead, he snapped a fanny pack around his waist, stuffing it with lunch and a clean pair of socks. "I figured I could dodge and I could run if I got into trouble," he recalls. "I'd stick with a Marine sergeant who knew how to move." Run, he did, the day a sniper shot and wounded the man next to him, a fellow from Nanakuli named Robert Nueko. With foolhardy bravado the 140-pound Krauss volunteered to carry Nueko's 40-pound pack as the company dodged fire in a dead run. "I was 40 and these guys were 20," he says. "We ran a quarter of a mile and my legs were trembling so much I thought they'd buckle. When we stopped to rest I said, 'I can't do this.' Well, Nueko was a big, shy, soft-spoken guy and he said to me, 'You can do it Bob,' and so I did." That night was spent in drizzling rain, with ants crawling up his legs, and no shelter, not even a poncho. Remembering the advice of one longtime war correspondent, he knew it was time to come home: "He told me 'You write great stuff, but be careful. You'll get too close and you won't be able to get out.'" Yet Krauss left with regret. "Our business can lead to some ironies," he says. "I really felt guilty for coming back, because they couldn't." Soon after returning to Honolulu, Krauss learned that Nueko had been killed in action. Turning against development Krauss' tenure at The Advertiser has paralleled the growth and maturation of modern Hawai'i. For years an unapologetic cheerleader of growth and tourism, Krauss was one of the first to state publicly that uncontrolled development could wreck Honolulu. His first book, "Here's Hawaii," was a huge success when it was published in 1960, and its charming stories drew thousands to the Islands. But as Krauss saw his favorite places bulldozed or trampled, he decided it would be hypocritical to keep making money by touting Hawai'i's charms in travel books. He decided instead to write about the culture, history and people of Hawai'i and the Pacific. His 14 books have sold about 150,000 copies. He has watched the rise of Hawaiian activism and pride, the rekindling of voyaging, the personality politics of five generations. With famed anthropologist Kenneth Emory as his "guru," he fell in love with the Pacific and helped advance knowledge about its vast reaches. One of his favorite stories involves an early voyage of Hokule'a to Mangareva, where much of the culture had been destroyed by a "crazy" priest. One of the things the Hawai'i voyagers did, he said, was to teach people how to blow conch shells again. "And you could hear all over the island '... brak ... grock ... gluck ...' " as people practiced, he says with a chuckle. Country preacher's son Advertiser library photo • 1999 His chronicles typically come from the warm and doughy side of things, from his advice to "wimmin" as a yuck-em-up bachelor in his 1950s columns, to the series of pranks and adventures he launched that helped create a strong personal identity for the morning newspaper through the years it struggled to survive. As he helped put Hawai'i on the map, he also put a face on newspaper journalism in Hawai'i: His own. Krauss, the son of a country preacher in Kansas, arrived in Hawai'i in 1951 with a journalism degree from the University of Minnesota and has applied a sense of wonder to life ever since. Almost from his first day at The Advertiser — working for $65 a week — he embraced this new and culturally complex world. "He was likeable," says longtime Advertiser columnist Tsuneko Oguri, who wrote under the name "Scoops Casey." Pretty soon, she said, he was coming up with wild assignments. "That's pretty much how Krauss operated ... The things he wrote about, he lived them." Krauss excelled at personal journalism and the creation of a public persona. By the 1970s, that persona had gained a classic green MG convertible, knee socks, Bermuda shorts and white shoes. Always white shoes. But he worked devilishly hard at it all, putting in 12- and 14-hour days. No matter what, at the end of each day's adventure, the column had to be done, sometimes six days a week, in addition to reporting on big stories like dock strikes, volcanic eruptions and elections. "I worked with him when he covered the waterfront and he's always been a very thorough, honest reporter and he is well respected by the business community," said Robert J. Pfeiffer, chairman emeritus of Alexander and Baldwin. "All of us have considered him a good friend." 'Anything ... to catch attention' Krauss' early columns, called "In On Ear," ranged from the amusing to poignant to the simply goofy, and from the early 1950s through the mid-1960s there were a good many "stunts" designed to draw attention to Krauss and the struggling Advertiser. He wrote columns from the top of Mauna Kea, a desk sunk in the bottom of a tank at the Waikiki Aquarium, on the beach, and about 40 Pacific atolls and islands. Early on, the column carried a series of photos of Krauss, including the back of his head. Another time it carried a month of daily mugshots — each in a different hat. "I was trying to do anything," he declares, "that would catch attention." In the wake of Thor Heyerdahl's raft voyage across the Pacific to claim Polynesians migrated from the Americas, Krauss and TV personality Kini Popo rode a makeshift raft down the Ala Wai to prove their own tongue-in-cheek migration theory: that the people at the Waikiki Yacht Club had come down the Ala Wai by raft from Kapahulu. "We called it the Kon Kini Expedition," Krauss said, chuckling. "We tied up traffic all the way down the Ala Wai. The cops were madder than hell." But the stunt that landed him in Time magazine in 1956 was the challenge to spend a day with a group of teenagers and then see what kind of advice he'd be willing to give about raising children. Taking the challenge a step further, Krauss suggested caring for four preschoolers for a week. The experience came in handy to raise his three children with his wife, Betty, a decade later. "We had a ball," he says of that time. Krauss, who is now divorced and lives alone in Honolulu, has four grandchildren. Saving Honolulu's history Krauss used his column not just for entertaining stunts, but to serve the public. In 1954, he collected money to send a 5-year-old Ma'ili boy to Philadelphia for surgery that saved the child's life. In 1963, he spearheaded a fund-raising drive to rescue the venerable square-rigger Falls of Clyde from being sunk as a West Coast breakwater. It was also his inspiration to turn the Falls into a maritime museum, and then see it become part of a larger Hawai'i Maritime Center 20 years later. And his wealth of knowledge about his town often makes him a court of last resort for all sorts of arcane detail. Recently, Advertiser copy editor Jim Richardson turned to Krauss when the archives didn't yield the whereabouts of a mysterious place on O'ahu called Watertown. Krauss knew: "Near the airport." Krauss shakes his head and seems almost sheepish talking about his half-century at the newspaper, as if he can't believe the time slipped by so fast. He has no plans to stop, and as often is the case, finds a story to tell why. "The thing I'm really afraid of is what happened to a guy named Gared Smith, who came here in 1901 and worked for the agriculture department before The Advertiser," he says. "Well, he got old and there was no retirement and no pension at that time, and the only way to take care of an old duffer like that was to keep him on." Smith wrote his columns, Krauss remembers, one painstakingly slow keystroke at a time. And every column sounded the same. "I made up my mind I'll never let that happen to me," he says. "I'll walk out before that happens. When the phone stops ringing, that's when I walk out."

Bob Krauss became known for his stunts, including setting up shop in unlikely places. Here he works from Waikiki with his "assistant."

In this Krauss stunt, he churned out his column from the bottom of a swimming pool.

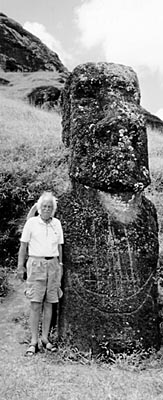

Krauss with the stone statues on Rapa Nui, where he traveled with Hokule'a.

© COPYRIGHT 2001 The Honolulu Advertiser, a division of Gannett Co. Inc.

Use of this site indicates your agreement to the Terms of Service (updated 08/02/01)